If American democracy is to be saved — from foreign intervention, partisan polarization, or pandemic infestation — its liberation may be found in the mobilization of elections. Forget mailboxes. Voting by smartphone is the answer.

Who better than Seattle’s champions of mobile innovation, the founders of such franchises in mobile communications as McCaw Cellular (later AT&T Wireless/Cingular), MCI (later Comcast) and T-Mobile, to be in the room where it happens. One phone, one vote — in fact, the revolution has already begun.

On Feb 11, 2020, Greater Seattle became the first region in the United States where every voter could cast a ballot using a smartphone — a historic moment for American democracy. The mobile technology was used for a board of supervisors election for The King Conservation District, a state-chartered natural resources assistance agency with territory that includes Seattle and more than 30 other cities. About 1.2 million voters were eligible to take part.

“This is the most fundamentally transformative reform you can do in democracy,” said Bradley Tusk, the founder and CEO of Tusk Philanthropies, a nonprofit aimed at expanding mobile voting that funded the King County pilot.

The idea of voting over the Internet gained real momentum after the 2000 Presidential election, when the country found itself in a constitutional crisis owing, in part, to faulty voting machines and mangled paper ballots with “hanging chads.” People were already shopping and banking online, why couldn’t electronic voting replace America’s aging election infrastructure the same way electronic shopping carts were replacing the ones with shaky wheels?

To serve the needs of the military, American citizens living abroad, and the disabled, every state is required to deliver ballots online; thirty-two states also allow voters to return them that way, too.

“If someone’s in a hospital bed, they’re not at home getting their mail, so we can’t mail them a ballot.,” explains Amelia Powers-Gardner, a county election official in Utah and one of the Government Technology 2020’s Top 25 Doers, Dreamers and Drivers, when interviewed by Techstars’ co-founder David Cohen.

“Also, it might be hard to verify their identity. But if they have a smartphone that has a thumbprint on it, then their phone can verify their identity for us, and we can ensure they’re getting the right ballot, and that they’re getting it in a timely manner.

Amelia is one who believes that the mailbox won’t save us. “We can’t turn a key and make vote by mail happen nationwide. What we can do is utilize a smartphone. The vast majority of Americans have a phone that they could use to securely vote, and then those that don’t, we could probably pick up the slack with vote by mail. But a lot of people aren’t looking at the logistics. It’s not as simple as a piece of paper and an envelope when you’re talking about a safe, secure election. Technology is scalable in a way that paper and pencil just isn’t.”

“The vast majority of people utilize their cell phone to do their banking, fill out the census, send money, and purchase items, ” she adds. “They put their most private information on their phone. The vast majority of people are excited about mobile voting and they want it, they just don’t happen to be the loudest in the crowd.”

Will Smartphone App Voting (SAV) Save Democracy?

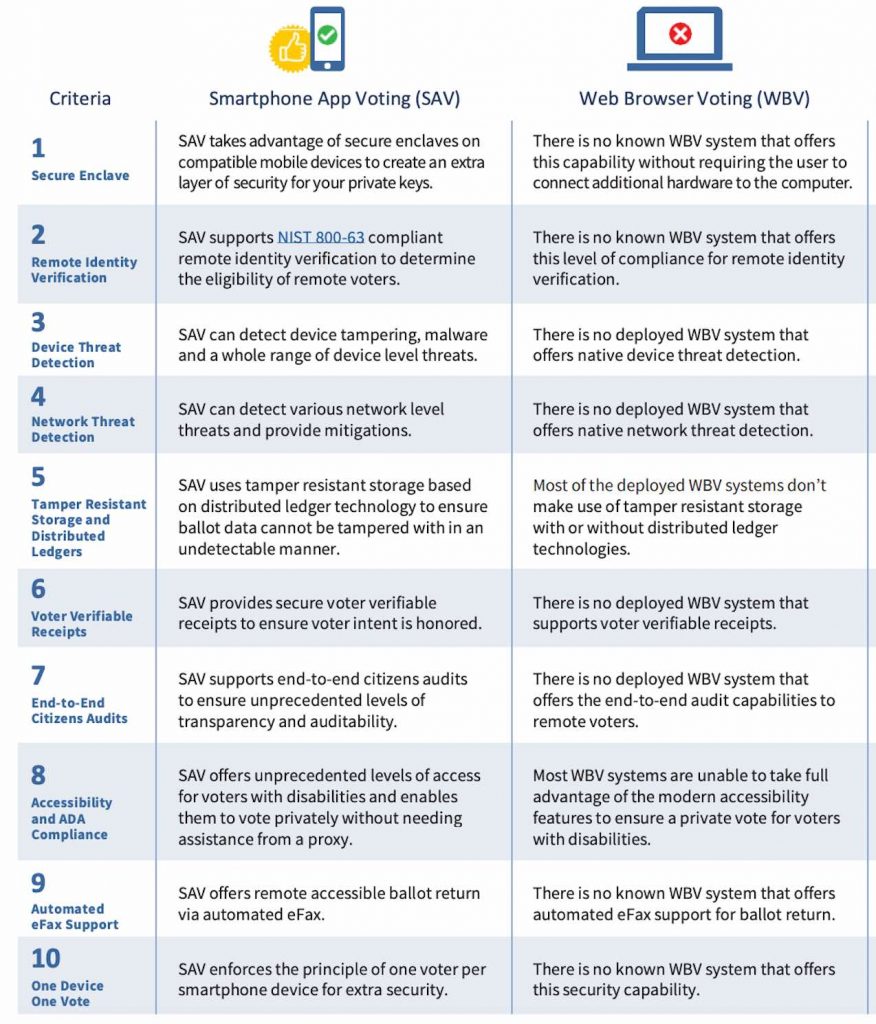

Smartphone app-based systems contain unique security features that distinguish them from web browser-based platforms (see chart below). These distinct features allow unprecedented levels of threat detection at both the network and device level, ensuring that a compromised device cannot submit a vote. This ability for advanced threat detection makes breaking into smartphones without physically connecting to the device resource intensive.

For example, an untethered hack of an iOS device has been referred to as the “million-dollar hack.” According to Wired — a zero-day hack of an Android system could cost up to $2.5 million dollars. In addition, smartphone app-based systems allow the ability to remotely verify a voter’s identity, offer enhanced accessibility features, and the ability to conduct a rigorous post-election audit to ensure integrity in the results.

Finally, smartphone app-based systems incorporate multiple layers of security to provide defense-in-depth, or at every layer of the platform. These include system-level security, network-level security, application-level security, and transmission-level security. If one layer is penetrated, the threat is detected and stopped at additional levels. In addition, malware detection and end-to-end encryption is employed to detect whether an operating system has been tampered with, and to prevent a compromised device from submitting a ballot.

In the landscape of all remote voting systems, security is still and always an ongoing journey and not a destination. It remains vital to continually test and identify possible vulnerabilities to ensure a comprehensive defense.

The critical issue that will finally vindicate “closed-loop” Smartphone voting isn’t the ability to deliver a ballot to constituencies, or to markup the ballot, but the uninterrupted return trip back to the voting database without being intercepted, corrupted or counterfeited.

Five days after a Washington D.C. election was held using OmniBallot software by Seattle-based Democracy Live, two computer scientists, J. Alex Halderman, at the University of Michigan, and Michael Specter, at M.I.T., released the results of an independent forensic analysis of OmniBallot. Their verdict was, in a word, chilling. In their estimation, the system was vulnerable to malware and manipulation on the return leg of the trip.

The two scientists were especially concerned that the contents of an OmniBallot, along with the identity of the voter, were being recorded by the software. If that information were to be leaked or sold, they wrote, it could be used for targeted political ads, disinformation, or coercion.

In his response to the report, Democracy Live CEO Bryan Finney noted that Halderman and Specter’s complaints “relating to the transmission of ballots and the possibility of a compromised device . . . is a universal critique of Web sites in general.”

The evoting Jeremiads were undeterred. Their next target was a blockchain-based electronic-voting system that was in use at the time in West Virginia, called Voatz. Specter and two other M.I.T. researchers were the authors of a technical takedown of Voatz, which resulted in its actual takedown by the state. Among other issues, they found that hackers could easily change votes.

It’s important to note that while efforts have been made to evaluate the risks associated with electronic voting systems, little effort has been dedicated to quantitatively assess the risks of the by-mail voting system, and to systematically compare them with risks of other voting scenarios.

Tusk Philanthropies has spent about two million dollars a year funding online-voting pilots around the country. There have been twelve so far. Founder Bradley Tusk, who was an early investor in Uber, worked in government as the communications director for Senator Charles Schumer, as the campaign manager for Michael Bloomberg’s third mayoral race, and as the deputy governor of Illinois.

“If you told me that we’re going to do mobile voting for every voter in the general election, I’d say that’s crazy,” Tusk said. “There’s a reason why we’re funding these very small pilots. It’s to test proof of concept without taking major risks.” Tusk remains resolute.

Microsoft to the Rescue?

A research project at Microsoft could be part of the answer. The project is called ElectionGuard, a free and open-source SDK from Microsoft’s Defending Democracy Program, a comprehensive effort on Microsoft’s part that includes providing tools for building electronic voting systems.

Defending Democracy has been working on voting software that attempts to solve the problem of trust through a mathematical process called homomorphic encryption. Standard encryption obscures information behind unintelligible strings of letters and numbers; homomorphic encryption enables those unintelligible strings to be added together while still remaining behind the veil. Applied to elections, this technology could allow ballots to be aggregated, tallied, and verified without the individual votes having to be decrypted. If it worked, voters could check that their choices had been accurately counted, without anyone else ever seeing them.

Even with end-to-end verifiability, the voting process remains at some modicum of risk. Microsoft is not challenging the existing business model of election vendor purity, some of which run their devices on Microsoft’s Windows operating system. Adding ElectionGuard to voting machines does not eliminate private equity’s ownership of the electoral system or take unsecured, impossible-to-audit voting machines out of circulation.

Vote-by-mail, which may become the preferred method of voting here and now in light of the global pandemic, presents its own problems, because filling out ballots in private at home or in the workplace could lead to the kinds of coercion that the secret ballot was meant to curtail. And the prospect of hacking by foreign adversaries—or by any bad actor—will always be present in a decentralized and inconstant system.

“I’m not going to claim that we have any way of securing elections, and that’s a problem,” Microsoft’s senior cryptographer Josh Benolah told the New Yorker magazine. “We’ve got an asymmetric battle with nation-state actors who are attacking little counties, and they can destroy data and they can corrupt data and they can do all sorts of things. But I am claiming that adding end-to-end verifiability makes any tampering with the data detectable—and not just by election officials, but detectable by you and me and candidates and news media and anybody else. And that’s a real value.”

Until mobile voting ultimately arrives online with the absolute security of point-to-point authentication and privacy protection, the best advice is to plan ahead. Now, more than ever, PLAN YOUR VOTE for the 2020 general election to give it time to be counted, and let vote-by-phone freedom ring! [24×7]