One of science fiction’s nobler virtues is reimagining the purpose and usage of technology. Arthur C. Clarke’s Newspad predated the tablet PC or iPad by a few decades. Earbuds were first described by Ray Bradbury in Fahrenheit 451, circa 1952. Mark Twain’s 1898 short story, From the ‘London Times’ of 1904, was set six years in the future and featured a device known as the Telelectroscope, a “limitless distance” telephone that could create a worldwide inter-network of information that would be available to all people.

The most powerful technology that is emblematic of a more advanced and enlightened society was animated on Star Trek in the form of the twenty-third century handgun, better known as the Phaser.

Captain Kirk’s phaser beam could cut through walls and burrow through rock. Phasers could heat objects, making them glow like coals, or slice through a hull. The Phaser could also disintegrate living creatures. But the greatest power of the weapon was its capacity to be harnessed — the ability to set the Phaser on stun.

Stunningly Silent but Not Deadly

The name Taser itself is an acronym for Tom A. Swift’s Electric Rifle (the Tom Swift books about an inventor of amazing gadgets were a childhood favorite of inventor Jack Cover). The name is also a registered trademark, owned by Axon. No stun gun, other than the Axon TASER, may bear the TASER brand name.

Like a Phaser set to stun, a Taser’s function is to immobilize a human target, not destroy it. It fires two small barbed darts intended to puncture the skin and remain attached to the target, at 180 feet (55 m) per second. The darts deliver a modulated electric current designed to disrupt voluntary control of muscles, causing “neuromuscular incapacitation.” A police taser typically peaks at 50,000 volts, and by the time it reaches your skin it’s only around 1,200 volts. It is not, underscore not, 100% risk-free but has been proven safer than batons, fists, take downs, tackles and impact munitions.

Having sold approximately 700,000 Tasers to “public safety professionals” worldwide, Axon estimates that the number of people that have been saved from death or serious injury because an officer used a Taser device to de-escalate a situation is in the hundreds of thousands.

When Atlanta police shot and killed Rayshard Brooks on June 12, 2020, the justification was that he grabbed a taser from an officer. Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms said that security footage appeared to show that Mr. Brooks had fired the Taser toward the officer, who was chasing him before he was killed, but that she did not consider that a justification for the shooting.

The mayor was entirely correct. The Taser did not pose the threat of deadly force.

To Taze or Not to Taze? This is Not Really the Question.

The recurring debate about the use of Tasers in law enforcement is confounding in that it argues the wrong question.

The issue can’t be a question of public safety. In no world is the crossfire of a .40 caliber pistol less risky than the probes of a taser. Any alternative to a ballistic firearm is, by design, safer and more humane.

Rather, the debate should be “Why are we shooting to kill?”

The purpose of law enforcement in any society is to create a path to justice, to enforce the laws, not preempt or substitute for them. Any action taken by a law enforcement officer that prevents our system of justice from being executed without due process is justice being denied.

As weeks of protests and marches across America demonstrate, by preempting the administration of our legal process the damage we do to our society is far greater than the crimes being alleged in practically every situation. Indeed, the use of deadly force following a routine traffic stop has blown a hole through the Constitution and Bill of Rights, demanding we reexamine the role of law enforcement institutions and reevaluate the role of a militaristic, warrior-like police force.

“Why” would we choose to use a weapon in community-focused, law enforcement efforts that is literally and figuratively overkill ?

Ramsey Clark, an American crusader for justice in the 1960’s as U.S. Attorney General, was a champion for abolishing the death penalty. His philosophy is no less relevant for the use of deadly force in apprehending a suspect.

“In the midst of anxiety and fear, complexity and doubt, perhaps our greatest need is reverence for life–mere life: our lives, the lives of others, all life. Life is an end in itself. A humane and, generous concern for every individual, for his safety, his health and his fulfillment, will do more to soothe the savage heart than the fear of state inflicted death which chiefly serves to remind us how close we remain to the jungle. “

“In the field of law enforcement, the use of force to apprehend an assailant has an obvious threshold. Lethal force achieves nothing in service to the law or to law enforcement.”

National Guidelines Must Replace Thousands of Individual Policies

Police forces across the United States currently permit a wide use of weaponry, often in situations that do not warrant such a high level of force. National guidelines are needed to standardize procedures for Taser use.

In a 2008 report, Amnesty International examined data on hundreds of deaths following Taser use, including autopsy reports in 98 cases and studies on the safety of such devices. The human rights organization believes the weapons should only be used as an alternative in situations where police would otherwise consider using firearms. Point well taken.

An in-depth investigation by the Reuters news agency found that of the more than 1,000 deaths following the use of the stun guns in the US since the early 2000s, autopsy reports have cited Taser shocks as a cause or contributor to death in only 153 cases. The devices should not be used in all cases, including when the subject is visibly intoxicated or when a known heart problem or other serious medical condition may exist.

Defund or Disarm the Police?

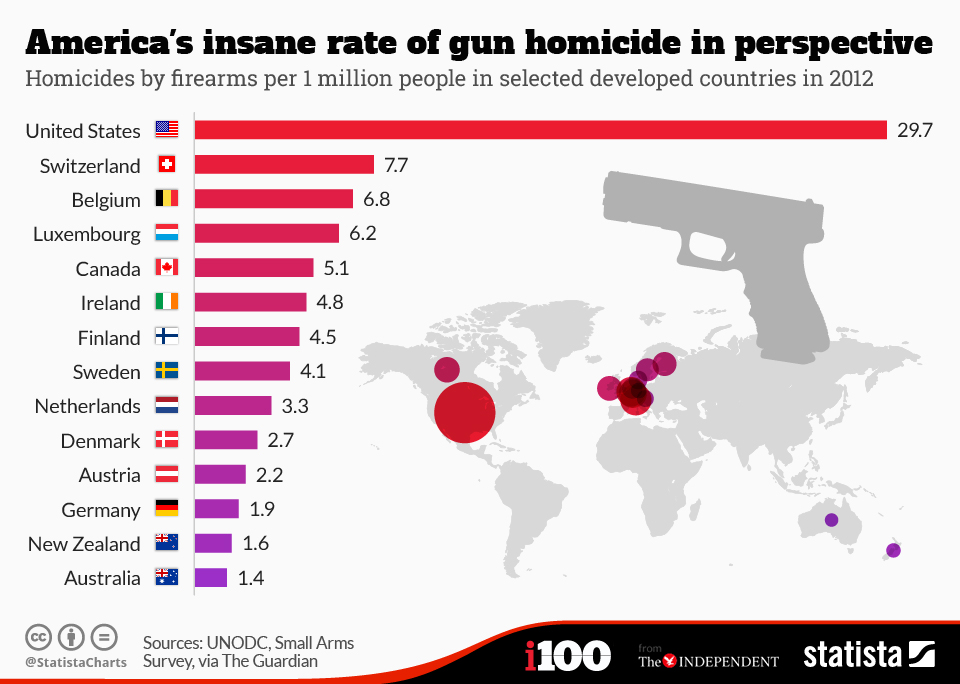

A jaw-dropping statistic is that for every 100,000 people, 4.43 deaths occur from gun violence in America, four times higher than the rates in war-torn Syria and Yemen.

Dr. Vin Gupta, a critical-care physician and scientist at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, tracks data on deaths from gun violence around the world.

Is there an example of a country that had a high rate of deaths from gun violence, then enacted legislation and saw a change?

When South Africa passed its Firearm Control Act in 20 — banned automatic rifles, instituted background checks, permits and licenses there was a 13.6% decline on average per year in gun-related firearm deaths. Austria passed a similar law and saw a similar result a few years before that.

Norway is one of 19 countries worldwide where police officers are typically unarmed, and permitted to use guns only in exceptional circumstances. These countries, which include the United Kingdom, Finland, and Iceland, seldom see deadly incidents involving police officers. While 1090 people were killed by police in the United States in 2019, Norway saw no deaths at the hands of police officers for the same year.

The 19 nations in the world that do not arm officers vary greatly in their approach to policing, but they share a common thread. “What we can identify in these countries is that people have a tradition—and an expectation—that officers will police by consent rather than with the threat of force,” says Guðmundur Ævar Oddsson, associate professor of sociology at Iceland’s University of Akureyri who specializes in class inequality and forms of social control such as policing.

Countries with a philosophy of policing by consent, such as the United Kingdom, believe that police should not gain their power by instilling fear in the population but rather, should gain legitimacy and authority by maintaining the respect and approval of the public. This model of policing maintains that uses of force should be restrained and success is measured not in how many arrests officers have made but rather, by the absence of crime itself.

Guns, Guns and more Guns

Writing in The Atlantic, Derek Thompson points out that “something is weirdly absent from the general discussion about police violence in America: the weapon most commonly used to inflict it.”

Violent crime has declined by more than 70 percent since 1993. But perhaps some police paranoia comes from the fact that the U.S. has added twice as many guns as people since the mid-1990s. “Generally, when a police officer pulls up to a car in Australia, they don’t expect someone to be armed,” Terry Goldsworthy, a criminologist at Bond University in Queensland, Australia, has said. Indeed, just 6 percent of Australian households own a gun. In the U.S., that figure is 43 percent.

“In a country where guns are protected by the Constitution and cherished by tens of millions of Americans, meaningful change will require a major social movement, writes Thompson.” Perhaps we’re seeing the seeds of that groundswell right now. As long as reformers are imagining the future of an unbundled police force, they have to be clear-eyed about the roots of civilian and police violence. Which means they have to talk about guns.”

“Police officers in the United States in reality need to be conscious of and are trained to be conscious of the fact that literally every single person they come in contact with may be carrying a concealed firearm,” David Kennedy, a criminologist at John Jay College, explained. “That’s true for a 911 call. It’s true for a barking dog call. It’s true for a domestic violence incident. It’s true for a traffic stop. It’s true for everything.”

This is one potential reason, experts said, that the US has far more police shootings than other developed nations.

Changing The Warrior Mentality

At Seattle’s Basic Law Enforcement Academy (BLEA), new recruits realize that the profession is flawed and that racism and brutality pervade its ranks.

“Everyone is talking about how we can make a change and be better,” said 24-year-old recruit, Tessa Vanderpool.

“If you ask almost any recruit why they want to be a cop, they’ll say ‘It’s because I want to help people,’” said Sean Hendrickson, the program manager for de-escalation training at BLEA. “I believe that it’s true.”

“But somewhere between that day and the pick-your-next-awful-video, we as a profession did that to that officer, made him that person,” Hendrickson said. “Institutional racism is a piece of that, and individual racism can be a piece of that. But make no mistake. We did it to him.”

All the good lessons and training provided at BLEA, which includes hours of de-escalation and less-than-lethal force training, can be stripped from a recruit by a bad training officer or a department’s “warrior” culture.

“Too often, the first thing they hear is, ‘Now, forget what you learned in the academy. Here’s how we do it,’ and that’s it,” Hendrickson said. Indeed, two of the four officers arrested and charged in death of George Floyd were trainees.

They are training with the wrong weapons. [24×7]